“I have written a series of articles on the subjectivity of perception, starting this week with a thorough thrashing of the colour brown.”

I’m afraid I have some bad news for you all. I am working on an art piece of such unimaginable opulence it is going to forever change the way we envision colour. My use of brown is - and this is no exaggeration - so magnificent that I have elevated brown to transcendent, holy, and untouchable state, forever unobtainable by the masses. To put it another way, you can no longer use brown. Sorry, I know many of you love brown so much you actually keep names that contain the word brown (as in that seminal piece of the western TV canon “Mrs Brown’s Boys”), but you are just going to have to go by a transient form until you can come up with a new name, such as “The [Person(s)] Formally Known As Brown”. Speaking of the colour purple I have half a mind to remove that transgression to the colour pallet and call it not-yellow, but I am hesitant to do so as it is Adam’s favourite colour and I owe him a favour or two. I do empathise, my favourite colour was also purple for a time, but I have recently decide to group every bright colour into one mega colour called “Chris & Alia’s Megacolour, Please Do Not Steal”, which is now my favourite. Incidentally, those Formally-Browns looking for a less pooey name are welcome to name themselves after my new colour, as long as they promise not to steal it.

This all seems rather irrational, but I would argue colours and colour terms (the words we use for colour we perceive) are irrational things to begin with. I chose to transcend brown, specifically because it is a fairly common colour; so common that Crayola used it in their first batch of crayons and still issue it as a “default” colour to this day. Although, brown is the Salford of colours; it exists as a distinct entity through distinctions not afforded to others. It is also the least tasty crayon- I'm not quite sure how I know that.

The evolution of Crayola, demonstrating it's evil brown-bias / Credit: mentalfloss.com

In the strictest sense, brown is to orange what light blue is to dark blue; they are shades of one another. However, brown and orange exist as separate entities whereas light blue and dark blue do not, or at least that is true in English. Some languages split blue into distinct entities, like Russian with it's “goluboy” and “sinnii”. Meanwhile, other languages - like Heian Japan and Ancient Greek - don’t acknowledge the colour as a distinct entity. This is because colour terms evolve with the languages that use them, new colours only emerging in a language when the culture that uses that language requires the distinction. Other than the sky, the Ancient Greeks had little access to blue things, so there was no need to draw the distinction. In The Odyssey, Homer describes the Aegean “wine-dark” colour, confusing many historians for generations afterwards.

However, to the Russian’s importing rich Chinese porcelain with a dark blue glaze, while also dealing with the light blue in the plumage of doves, there was a need to not only distinguish blue as its own entity but also to distinguish between the two. Moreover, colour had only become important relatively recently; to seventeenth century peasants battling each other over a grain of corn the colour of the cesspool they fought in wasn't of particular importance. However, to the aristocrats defining themselves with the stuff they own it was vitally important that the dress they bought was blood orange, not red.

Blue as we know it didn’t really enter common English until the eighteenth century, popularized through Newton’s colour spectrum and the blue that servants had to wear. It might have its roots as far back as Chaucer, but it certainly wasn’t in common usage and Chaucer probably just forced the term for use in a rhyme. The problem with it back then was that it wasn’t a common term, and at the time it was used with the awareness that it wasn't an English term, but a loanword from the French. This serves as concrete proof that writers tend to use and talk about other languages to elevate their writing. Hello, by the way.

The Shrimp Girl, Henry James Johnstone Cc Manchester City Galleries

You can thank this style for helping popularise blue with the common folk

It seems counter-intuitive, but separate and isolated languages develop colour terms in spookily similar ways, so similar they can be organised into a hierarchy as described in a study by anthro-linguistics Berlin and Kay. That study differentiates distinct terms from associative colours (eg; Earthy, sky-coloured, ect.) and then organised languages into a hierarchy dependant on how many colour terms are commonly recognised by the people that speak the language, before seeking patterns in that hierarchy. In the early stages, the first colour terms developed were simply light and dark colours, grouped together in what I like to call megacolours. After developing dark and light, colour terms languages developed a term for red, then either green or yellow, then both green and yellow, then blue, and penultimately - before blossoming into broad and eclectic palate of terms - brown.

That’s right; brown. That colour that is found literally everywhere had typically developed after the term for blue, for green, for almost every other common colour term. This seemed mind-boggling to me when I first found out about it, here inundated with brown crayons and all of a sudden I find we only just came up with the things. It seems hard to operate without it, but people and the way we communicate are hardier than that. Without brown, the vibrant browns we know today then get reorganised; dirt becomes blackened and Earthy, rust becomes a vibrant orange, and poop… well poop becomes poop and browns can be all the richer without the association. The reality is, without brown, language becomes prosaic to our ears, more useful too when we aren't grouping all highly-saturated dark colours under a nebulous “brown” super- group. Without it, language becomes nothing if not more colourful.

This is all to say I think you will do fine without brown, but there are those - however - that might reject my assertion of the subjectivity of colour, that colour is a physical thing grounded in objectivity and though people didn’t have words for the things they were seeing surely they still saw it, right? “Chris, you beautiful creature,” I can hear you all say, "a rose by any other name!” Well no, but I have rambled enough for one day and I will disabuse that notion next time. Until then please remember; avoid purple, adopt the Chris & Alia’s Megacolour; Please Do Not Steal, and - of course - leave brown in the past.

Oh and as for the transcendent masterpiece, you are just going to have to wait. I am not yet done with it. For some reason several of my crayons vanish on the nights I get drunk.

Image 1: The Desert Edwin Landseer R.A. (1902) © Manchester City Galleries

Image 2: English School (c.1780) © Manchester City Galleries

Image 3: Temeside, Ludlow Charles Ernest Cundall (1923) © Estate of the Artist/Bridgeman Art Library

Image 4: The Lady in Brown Jean Hippolyte Marchand © Manchester City Galleries

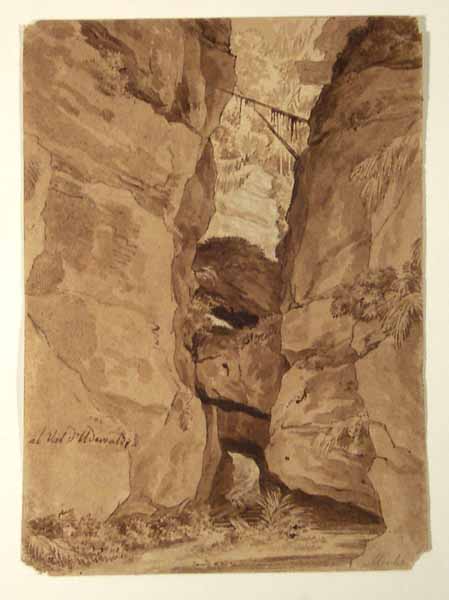

Image 5: View in the Campagna, Rome (with ruins) Edward Lear (1988.136) © Manchester City Galleries

Image 6: A Spate in the Highlands Peter Graham 1866 © Manchester City Galleries // On display currently in Gallery 8

Image 7: 1940-5 © Manchester City Galleries

In the following article I will discuss language’s influence on the perception of reality. I hope to go on to discuss art’s use of language in a follow up article to that one, focusing on how it influences people’s perception of art.

Crayola’s evolution: http://www.slate.com/blogs/business_insider/2014/10/05/crayola_chart_how_many_crayon_colors_have_been_added_to_crayola_box_since.html

Newton & The Colour Wheel: http://munsell.com/color-blog/sir-isaac-newton-color-wheel/

The History of the Colour Brown: https://blog.oup.com/2014/09/brown-etymology-word-origin-part-1/

Colours of the Medieval Rainbow: https://forthewynnblog.wordpress.com/2017/11/20/how-many-colours-were-there-in-a-medieval-rainbow/

Russian Speakers and the Colour Blue:

https://www.newscientist.com/article/dn11759-russian-speakers-get-the-blues/

The Study mentioned above:

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1876524/

Colour Perception and the Ancient World (Dark Wine): http://clarkesworldmagazine.com/hoffman_01_13/

Wikipedia; colour terms: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Color_term

Etymology Online; blue: https://www.etymonline.com/word/blue

Etymology Online; Gravity: https://www.etymonline.com/word/gravity

Ao and Midori: https://www.nihongomaster.com/blog/learn-traditional-japanese-colors/